Third Cinema Updated: Exploration of NomadicAesthetics & Narrative Communities

The notion of Third Cinema first arose in the charged political climate of the 1960s. The original ideas of Third Cinema, as with all such political and aesthetic movements, were a product of both the social and historical conditions of the time, particularly those prevailing in the “Third World.” Poverty, government corruption, fraud “democracies,” economic and cultural neo-imperialisms, and brutal oppression affected many Third World countries. These conditions required an appropriate response, and radical revolutionary movements rapidly sprang up to contest reactionary politics and to champion those whom Franz Fanon called “the wretched of the earth.” Third Cinema was in many ways an effort to extend the radical politics of the time into the realm of artistic and cultural production.

From its origin Third Cinema therefore was linked to revolutionary political struggle and particularly to political struggles in the Third World. For example, the Argentine filmmakers Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, authors of Towards a Third Cinema, used the term to describe films, like their own Hour of the Furnaces, that sought to break both from the traditions of Hollywood on the one hand and European art films on the other. These films were often revolutionary not only in the political statements that they advanced, their “content,” but also in their formal construction. They exposed the arbitrary rules underlying traditional filmmaking styles in much the same way that they worked to bring repressive social and political structures to the consciousness of their audiences.

This early, revolutionary period of Third Cinema deserves to be remembered and eulogized. Its spontaneity, groundbreaking formal innovations, political commitment, and the visceral impact of these films serve as an archival memory that filmmakers of today continue to draw upon. Yet, while these roots remain important, Third Cinema can no longer be defined solely in terms of its radical beginnings, its ancestry. While we should honor and draw strength from these cinematic inheritance as we do our own flesh-and-blood ancestors, we cannot live in the past. Third Cinema was always a cinema of change; to define it simply in terms of its original ideas is to reduce it to the status of a static historical phenomenon: something past or dead. Third Cinema, however, continues to live on, and like all living things, it cannot stay the same.

In considering the ways in which Third Cinema has changed, we should first of all acknowledge that the world has itself changed a great deal since the early days in which Third Cinema was born. Like the idea of the Third World, the very concept of Third Cinema was formed as an alternative to the great political oppositions of its time: First World capitalism and the Second World of the Soviet bloc. With, however, the collapse and implosion of the Soviet empire, we have been left with an idea of the “Third World” that no longer stands in contrast with a First and Second Worlds. Similarly, at a cinematic and cultural level, the rise of globalization has effaced many of the traditional distinctions between entertainment and art that Third Cinema sought to bring into question. The opposition between First and Second Worlds has given way to a universe in which the forms of capitalist globalization seem to hold sway everywhere. This global universe presents itself as an all-inclusive world, able to encompass all manner of cultural and political diversity. Yet, in this global world, new enemies have to be found, or invented. This need for a new oppositional structure has been met by the figure of terrorists and other “evildoers” who might threaten the security of the New World Order. Of course, these dangerous "others” are almost invariably linked to the Third World. Thus, the binary opposition of “us” and “them” has increasingly been cast in terms of the distinction between global capitalism and elements of the Third World. Whether one feels allied to one side or the other of this opposition, the other side is inevitably seen as endangering “our way of life.”

Resistance to the pervasive structure of global capitalism continues to be necessary, just as resistance to earlier forms of global imperialism was. Revolutionary opposition to new imperialist conditions was, of course, part of the historical moment in which Third Cinema was born. In the changed world of today, however, I would like to suggest that this form of oppositional politics and thought has become more problematic. For when resistance hardens into the form of binary oppositions, we have in fact adopted the very structure by which global capitalism operates. Global capitalism requires an other, an enemy, in order to constitute itself as universal and homogeneous. To accept this oppositional mode of thought is to become a part of the same kind of binary structure. To the extent that Third Cinema continues to espouse the rhetoric and thinking of its early days, it is fighting with a phantom that gains strength from every opposition. Hence, Third Cinema becomes not an alternative to Hollywood or capitalism, but merely its mirror, its other.

If we are to avoid this kind of oversimplified oppositional thinking, we must rethink the terms under discussion. I think that, in reality, it is quite easy to make the argument that, despite their rhetoric, neither Third Cinema nor the revolutionary movements from which it sprang were monolithically oppositional. Their positionality was never entirely fixed. Their resistance was always a mixture of different positions, different affinities, different approaches. Indeed, they provide a good example of what we today might call “composite” politics, in which many group identities and affiliations intermingle and overlap. One of the great mistakes of “left” politics has always been to imagine itself as pure and unambiguous in its oppositional stance. Rather than setting itself simply in opposition to capitalism, a composite politics, by its nature, works to disorganize the rigid “Us versus Them” structure upon which globalization, imperialism, and other forms of oppression are based. Third Cinema, at its best, always drew its strength from this sense of complexity, diversity, and multiplicity.

Narrative Communities

One way of illustrating the mixed, composite character of Third Cinema is through the notion of narrative communities. Such communities are defined not by some essential characteristic, but by the narratives or stories that they collectively share. Narrative communities need not, therefore, be unified or homogeneous. Various members of the community may identify deeply with one story, or one aspect of a story, and not with other narrative elements. Such communities are always a collection of diverse affinities, interests, and identifications. They are always, in other words, composite, mixed, even if they at times find themselves unified around some particular idea or action.

Narrative communities, however, often coalesce around particular stories or types of stories. One example of this kind of coalescence can be found in Hollywood cinema. The community that constitutes itself around Hollywood narratives is based on identification with a particular kind of story. Such stories must focus on individual characters, with narrative actions clearly presented, and must conclude in a way that resolves all plot conflicts, generally with the hero triumphing over the villain, good over evil. In short, then, Hollywood narratives are based on identification with a hero who represents “us,” set in contrast to a villain, an enemy, who can be destroyed in order to make the community whole. Similarly, stories that do not conform to these standards are considered to be flawed examples of filmmaking, outside the boundaries that define the community. Both at the level of the stories themselves and the audience's acceptance of these stories, the Hollywood narrative community is based on maintaining rigid boundaries between good and evil, inside and outside. This is, in other words, a community that defines itself through opposition, through the exclusion or destruction of a shared enemy or Other.

Some might argue that all communities are to some degree exclusionary. Yet, is it truly impossible to have a narrative community that maintains an openness to the stories of other cultures and peoples? What kind of stories/narratives can be told that do not depend upon an oppositional or exclusionary mode of thought? Third Cinema, I would argue, offers a glimpse of this possibility.

While mainstream entertainment cinema retains its emphasis on individual psychology and action, set against an often hostile world, Third Cinema has generally emphasized social problems and collective actions. Issues such as social justice, racial and gender equality, and the spreading of wealth and power become more important than individual achievements and wealth. At the same time, the division between “us” and “them” is often de-emphasized in Third Cinema. This is not to say, of course, that Third Cinema films never portray villains, but this villainy is not represented as the result of some essential individual character flaw, but as evidence of larger structural problems within the society. Today, moreover, many narrative communities have become more media-savvy than they might have been at the outset of Third Cinema. They have become much more adept at adopting/adapting various media for their own uses, at mixing stories and media forms from different cultural heritages. Accordingly, the tactics of Third Cinema have changed, becoming based less on oppositional strategies than on more complex, more mixed, more ironic, forms of resistance. Similarly, the communities that are constituted around Third Cinema have also become less fixed, more heterogeneous, as different cultural forms and memories have come to be juxtaposed and combined. In a sense, Third Cinema has become an increasingly creolized form, in much the same way that peoples from various parts of the Third World have found themselves intermingling in the metropolitan centers of “developed” countries. Indeed, the myths and stories from these different cultures have not only been combined with one another, but with aspects of Hollywood and European cultures as well. These narrative communities are dynamic and changing, open to diverse cultural influences. They are complexly multicultural and, for the most part, non-exclusionary. Unlike Hollywood, they do not rely on the figure of the Other to define themselves.

Third Cinemas

Today, the multivalent, composite character of Third Cinema and its narrative community has gained particular resonance as a means of resistance to global capitalism. For the inverse side of global centralization is to be found in the movement and mixture of peoples and cultures. Thus, just as with diasporic movements of people, Third Cinema has also spread, crossing oceans and national boundaries, moving to new places, adapting to new conditions. As it has moved, it has also changed. From its historical roots, a variety of new forms, styles, and approaches to filmmaking have come into being. Third Cinema has branched out, diversified, multiplied. Third Cinema can no longer be defined as a singular, univocal idea if, indeed, it ever could. It has become more complex, multifarious, heterogeneous. Third Cinema, in other words, has become Third Cinemas.

This distinction between the singular concept of Third Cinema and the plurality of “Third Cinemas” is, to some degree, no more than a change in emphasis within the original ideas of Third Cinema, but it also indicates an important conceptual shift, which responds to fundamental changes in the contemporary world. If early Third Cinema was resolutely oppositional in its stance, the idea of Third Cinemas implies a more multifaceted resistance to power. One might say that the concept of Third Cinemas suggests a more dispersed positionality, but only if one conceives of dispersion as a multiplication rather than as a loss of political will or a diminution of social forces. As, moreover, Third Cinema has moved, traveled, relocated, spread, it has become more than simply a Third World phenomenon. It has crossed the lines of geography, culture, class, race, gender, and religion, moving into the First World, into 'white' and other 'privileged' areas, where it has combined with other cultural forms, becoming increasing hyphenated, intermixed, composite. Third Cinemas are precisely a matter of these multiple, nomadic, diasporic forms and identities.

At the same time, however, the concept of Third Cinemas has also moved into other forms of media beyond cinema, including video, music, computer programs and video games. Third Cinemas cannot therefore be defined simply as a matter of “cinema.” The concept needs to be expanded to include various electronic and digital media. Third Cinemas, one might say, are mixed in terms of media as well. This expansion of the idea of Third Cinemas is not, however, merely a matter of taking into account new technologies. This multiplication of technological forms serves to match the sense of cultural heterogeneity that was inherent in Third Cinema from its beginnings. Third Cinema was never just a matter of producing films; it was always concerned with the cultural and political contexts in which cinema took place. There are many cultures, many forms, and many cinemas, within Third Cinemas.

So, while it is very important that the concept of Third Cinemas maintain and conserve many of the ideas that defined early Third Cinema, it must also be conceived in a way that allows space for a variety of approaches, styles, and projects. Here is where the idea of a third vision becomes powerful, needed and useful, for in stressing heterogeneity, mixture, multiplicity, irony, differences, it enables us to see and conceive of our relationships to one another and to the world in ways that are not dependent simply on binary oppositions. This multicultural, polyvocal status of Third Cinemas need not, I stress, imply a loss of political commitment (as is sometimes claimed), but rather a multiplication of modes of resistance.

But also, importantly, Third Cinemas provide an alternative third space where we can engage in ideas about imagination, about dreams, tales, and magical vision. Inasmuch as so-called oral and/or traditional cultures were not as strongly bound to oppositional Western thinking, they always provided an opening to this more mixed social or collective imaginary. And while there are many who are skeptical of the linkage between oral cultures and electronic culture, or information culture, I believe that there is indeed a worthwhile connection. Of course, mainstream media attempts to continually reinstate clear vision and boundaries and oppositions in, say “cyberspace,” to mark it clearly, to make everything easily navigable, yet it still has difficulty keeping everything in check, flowing smoothly. Consumer or cyberspace culture is based on organized choice, organized freedom. A third approach here would embrace a more dispersive, disseminatory, disorganized or complex movement. Complexity and mixture allow magic to take place, because they do not try to organize everything into rational categories, but instead rely on emotionality, paradoxes, ironies, etc. And what is magic, ultimately, but mixing and connecting things that do not seem rationally connected?

Off-screen: Third Space

What is called ‘magical’ is concerned with those aspects of life that cannot be easily explained in rational terms. Magic is that which seems to escape the gauges and instruments of scientific-technological thinking. Magic is, in other words, concerned with what lies beyond, with the invisible.

Cinema, of course, is generally understood in terms of the visual (or the audio-visual). In films, the visual field is defined by the frame. When we go to the movies our attention is generally focused within this frame; it is like a funnel that draws our eyes into the screen. The movie shapes a given field of view inside its rectangular frame; it distinguishes what is relevant from what is not; it concentrates movement into distinct objects; it defines the world depicted on the screen. Yet, at the same time, the frame also inevitably implies something outside itself; it suggests a relation to something that exists outside of the frame.

That which lies outside of the frame, outside of our immediate view, provides a means through which multiple meanings can enter the frame. In every framing of a given field of vision, there is inevitably a shading out of that which is outside the screen. Yet, when something is not on the screen, it does not mean that it is not active within the cinematic relationship, within the minds of the audience. Although the space outside the frame is usually considered to be “invisible,” it is an active presence that is open to the process of interpretation by the spectators. In other words, the area outside the frame provides a “blank space” that the spectator helps to fill in. This “blank space” is not only where the magic of cinema takes place, it is also the place that provides the spectators with multiple options to participate and even to assume a role as co-authors of the work. The “blank space” is a crossroads where we discover movements -- of spreading out, of moving in many directions at once -- not towards the center, but towards the margins.

What does this off screen space mean to Third Cinemas? It means that a “true” Third Cinema thinking, a more thought-out and reflective Third Cinema, would issue from both sides of an opposition onto a third space - the "blank space” -- the place of imagination and conjunction. This third way steps beyond the mere oppositions of seen and unseen and becomes a way of both disorganizing and complexifying not only cinema, but the world. In other words, in redefining Third Cinema, we are also defining it as a Third way of seeing, one in which allusive, imagistic, poetic, and magical styles enter the imagination. It is in this third space that these styles become ideas with a life of their own beyond anything the filmmaker might have imagined.

Third Cinema: The Elements and the Senses

I give you this one thought to keep – I am with you still –I do not sleep

I am a thousand winds that blow, I am a diamond glints of snow,

I am the sunlight on ripened grain, I am the gentle autumn rain.

When you awaken in the morning’s hush, I am the swift uplifting rush

Of quiet birds in circled flight. I am the soft stars that shine at night.

Do not think of me as gone – I am with you still – in each new dawn

—A Native American Prayer

Theorizing Third Cinemas requires us to rethink our relationship to the movements of different cultures and peoples, to the environment around us, to our notions of the world itself. The value of theory is always dependent on the terrain in which practice is carried out. Certainly, the situation in the world today has changed markedly, which suggests that what we need is a new geography, a new way of understanding what has been called Third Cinema. We must not only look at the world differently, but also write about it differently and in a variety of new and unexpected ways. If Third Cinema is multiple, writing about Third Cinemas must also take different paths. The journey is itself the destination; the writing is itself the theorization.

There can be no single “Theory” of Third Cinema. Third Cinemas tend to elude categorization. Writing about Third Cinemas must therefore involve an attempt to participate in the subconscious of these works, an effort to move with them on their aesthetic journey. Respect needs to be paid to the stories that they tell, in much the same way that people in many cultures respect the voices of their spirits and ancestors. Third Cinemas show us the connections, both visible and invisible, that link us and tie us to the world. Thus, Third Cinemas often pay considerable attention to aspects of the world that Western cultures tend to take for granted. These aspects are often figured in metaphors and allegories, which serve to express ideas and senses that cannot be articulated in conceptual terms. Yet, it is worth remembering that these stories, metaphors, and allegories are theories too. In what follows, I explore a few of the more prominent metaphors and stories of Third Cinemas.

Third Cinema as the cinema of elements

There are numerous instances in Third Cinemas where the natural elements acquire singular importance as punctuation in cinema and as essential components of the structures of producing meaning. The difference between Third Cinemas and other kinds of cinema can be located in their differing contexts. Third Cinemas generally present their characters less as discrete individuals than as parts of a larger environment, culture, or world. This larger context is commonly figured in elemental terms: water, fire, wind, and earth often play a major role in Third Cinemas. At one level, these elements frequently appear in Third Cinema films as allegorical symbols that stand for larger themes and issues. Yet, they also have an important presence in themselves, a presence that cannot be simply or easily explained. These elements are not simply physical objects. They are not, as in Western science, definite substances that can be categorized in a periodic table and used for instrumental purposes. Rather, they serve as the very material -- the elements -- from which the cinematic world is made. These elements, in other words, form the cinematic environment. Thinking of Third Cinema as a cinema of the elements suggests a respect for, an awe and wonder at the natural -- and sometimes supernatural -- environment. This respect for the elements is also a respect for our senses, which are inseparable from the world around us.

In the mainstream media, we are made to feel that 'sight' and 'sound' are the most important of the senses. Sight and sound are the senses that are most easily reproduced via technology. Touch, smell, and taste, on the other hand, are more subtle and complex and are not easily reproducible mechanically. While the valorization of sight and sound is accepted in a Western context, it is the subtle senses that are valorized in the context of many non-Western media practices. For instance, with 'touch' we gain access to both temperature and shape, and when we close our eyes we see in our mind's eye. Taste and smell are similarly subtle, and difficult to translate into words, sounds, or images. Technology can only with difficulty reproduce these senses; they seem to elude the conceptual and binary categories on which Western notions of sight and sound depend. Of course, no film could ever represent touch, taste, or smell directly. In Third Cinema films, however, these senses are often evoked indirectly. This sensory evocation suggests that there is more to Third Cinemas than what appears on the screen. We sense that something seems to be hovering just beyond our vision, our hearing: a ghostly presence, a material spirit, which is repressed or denied in Western cinemas.

Elements are not merely physical building blocks, ready for use by human beings. They have, one might say, a life of their own, which must be respected. It is precisely this elemental life that distinguishes Third Cinemas from most Western cultural forms, where the environment is staged as a mere backdrop for the actions of individual characters. This elemental presence is not, in fact, purely material. Wind, fire, water, and earth move us into a more complex, less definable realm, the realm of the unseen, of the spiritual. Indeed, elements in this sense connect the physical and spiritual, the seen and the unseen, the outside and the inside, the world and ourselves. For these elements are also part of our being. We too are products of the four elements. Third Cinemas acknowledge this sense of elemental connection.

Third Cinema as Collective Witness

In the annals of Third Cinema there are many examples of the power of the visual to tell stories that had been submerged in the cascade of commercial cinema. Of particular interest here is the case of the Rodney King beating, the subsequent riots, and the national and international outrage that grew out this event. The initial incident, accidentally caught on portable video by a non-professional videographer, had a profound impact. A similar spontaneous recording occurred around mid-2002 in the beating of a black teenager in Inglewood by local police. One might find many other examples from around the globe, even in the heavily edited daily news coverage from the Middle East and elsewhere. What connects these recorded images is the fact that they are, in a sense, unparaphraseable. This is not to say that they cannot be cited, repeated, as they frequently have been. But these citations or repetitions resist summary or categorization; they stand on their own; they exert their own curious power over their viewers. Who shot them or produced them is no longer a relevant question. Here, witnessing becomes a collective, rather than an individual, action. This act of witnessing is at once anonymous and public, unexpected yet very significant.

This witnessing via the video camera has become a sort of substitute for a third cinema style of filmmaking. Portable cameras allow stories to be developed almost instantly, not before but after the clip of the visual is seen. It is in the viewing that simultaneous contesting “meanings” come to be debated in the public sphere. Thus, in a different form, Third Cinema continues to serve as guardian and witness for the under-represented and marginalized, for those whom the system has relegated to the fringes of society, the fringes of the frame. In other important ways, it serves as guardian of those essential qualities of democracy and social justice which empower the citizen to undertake the active role of filmmaker, producer and witness. The style of Third Cinema thus empowers the powerless and the powerful by bringing actions and ideas into view, and hence into debate. Such a role is crucial to any possible notion of participatory democracy in the circumstances of today.

Third Cinema as Performance

Third Cinema is a type of performance art. Performance is an element of all cinema, but for Hollywood-style films, performance is generally relegated to the realm of acting. In Third Cinema films, on the other hand, performance becomes a basic aspect of the filmmaking process itself.

In this respect, Third Cinema is closely related to jazz. Jazz, in its essence, is live music – that is, it is live in the sense that it provides a space for complex interactions and improvisations. Spontaneous vibrations flow from and through it. Third Cinema, as a relational art today, seems to perform in a kind of dominant, up/down or minor/major key. Third Cinema practices like music should not be seen as merely a product but as a system of interaction, as a type of performance art, as a process -- which jazz is, which blues is.

Third Cinema is a relational art in that it also allows the spectator to create new relations, open new horizons, new possibilities of engagement with the work in whatever format it may be between filmmakers and film viewers. The aspirations toward audience participation and interaction among early Third Cinema filmmakers were very valid, and remain important for artists today. They wanted the social context of their work to be included within it; they wanted a distribution environment that were more varied and more open. These were valid concepts then and they remain valid today.

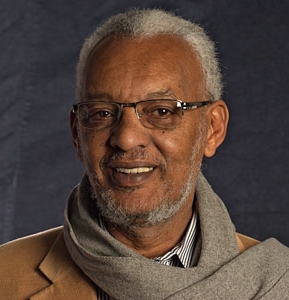

Teshome Gabriel, Ethiopian-born American cinema scholar, longtime professor at the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television, and expert on cinema and film of Africa and the developing world.

Teshome Gabriel, Ethiopian-born American cinema scholar, longtime professor at the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television, and expert on cinema and film of Africa and the developing world.