Stone

“STONE”

“Don't mistake the finger pointing at the moon

for the moon itself."

-- A Buddhist Saying

It is common knowledge that stones do not lend themselves to speech; but because stones are mute, it does not mean that they do not speak; they actually do, only they speak in a language that we do not recognize, that we do not know. The question then is: can we translate their silences to our language? Stones, as tools, have been associated with early technologies, from weapons to buildings to games. They have also been associated with writing, and with painting, providing early humans with surfaces to write upon and screens on which to create the first images. Stones are also the tablets on which spiritual messages were transmitted. Stones carry within them not just a material composition, but also a virtual one, a sense of what can be actualized.

There are other links that we can visualize in stones as well, though more disjunctive or perhaps mysterious ones: with the elemental forces they signify, as seals for political and religious matters, and for decorative and aesthetic purposes. The physicality of stones might be seen as an impulse to rethink the concrete and to re-imagine the empirical. What is being suggested here is that stones may serve as bridges to ideas, concepts, knowledge, locations. They give rise to what we might call a poetics of life. Stones are often seen as the most substantial of forms, yet their metaphorical bearing emphasizes their fluidity. Poets have known throughout time that elemental factors must be heard and addressed. The Egyptian poet, Zion El Abdin Fouad, in his poem entitled "Belted in Oppression: A New Song for Cairo," writes:

Are the roads getting white hair?

Or is it me who has grown old alone...

The river of age is running, escaping into the alleys...

I flood sand and stone.

Stones rubbed together create sparks and fire. The connection of stones to the senses is evident in that stones are often kissed, from the Blarney Stone to prelates’ rings to pilgrims’ rituals. Stones constantly make noises, whether in action with the wind, with water, with animals, or with human beings. Considered more broadly, molten lava can be seen as the stone’s "in-between" -- a state in which the fluidity inherent in the stone comes to life. In lava, stone is transformed from a symbol of being to a signifier of becoming: it changes the shape of the planet, demarcates powerful changes taking place below the surface. It therefore opens the space for a new hermeneutics of stone reading.

Here, the solidity of space can be reconsidered in terms of movement and mobility. Movement is not just a spatial displacement, or a matter of sequence, or of a linear history. While stones are generally associated with immobility, those that tend to remain still are in fact the ones that move the most throughout history. By not moving at all, they move in other directions, in other dimensions, in their own curious and often ironic way. Pyramids would seem to be the most immobile of things, yet they have been all over the world; there is no place in the world that does not carry archival memories of pyramids, for whom the pyramid does not signify something of deep cultural importance. One can argue that the same forces are at work in the Wailing Wall of Jerusalem and the Great Wall of China, and the Kaaba/Ka'ba of Mecca. Stones, like sacred relics, travel and induce us to do likewise; they move us emotionally, spiritually, and in many other ways.

Another form of travel would be that of the stone objects, marbles, and obelisks that were carted off to Europe and America by colonial powers and installed in their own locations as part of a different cultural heritage. These objects have been narrativized by European poets and statesmen who assumed the mantle of guardianship for these objects. The stone objects that have been sequestered under European control are supposed to convey a grand historical narrative that leads to their present circumstances, but in this context, they actually say something quite different. Here, we must listen to the narratives that lie buried within these stones, including narratives of dispossession and displacement and resistance. If we listen carefully to these stones' subdued eloquence, what they convey is no more and no less than their forced isolation, their imprisonment, their silencing. They cannot now move, or change, or speak as they would have otherwise.

****

Despite appearances to the contrary, stones are always in constant movement, whether they serve as paving stones, or appear in the hands of Palestinian youth, or are placed in the mouths of nomads in order to slake their dryness as they travel through the desert. Stones also have a powerful connection with water, providing the banks and shaping the trajectories of rivers and streams around the world, as well as forming beaches in many places.

We look to the impermanence of the world’s cities as ruins in the making. We are left with an impending legacy of memories of structures that appear to be sturdy, but which are in the process of becoming ruins. This certainly gives a sense of the transitory nature of many of the forces at work in the world and tends to propel us into a different modes of thinking about what constitutes the narratives of 'nations' and 'narrations.'

In demolishing the twin stone statues of the Bamiyan Buddhas, the Taliban sought to destroy the symbol of peace that the statues celebrated. Yet, the symbols remained in the imaginations of the world. Ironically, news has surfaced that a much larger statue of a reclining Buddha lies buried beneath the earth very close to the site of the destroyed statues. No doubt, the earth will continue to bear witness to other stories, other secrets, other memories.

Sir Richard Burton, who translated the Arabian Nights tales, is buried within a Bedouin tent carved out of stone in London. For Burton, this stone resting place signals an ironic end of his wanderings around Arabia. Multiplying these ironies, the Zimbabwean poet Musaemura Zimunya addresses Burton as well as himself in the following epitaph:

And behold these stones,

The visible end of silence,

And when I lie in my grave

When the epitaph is forgotten

Stone and Bone will speak

Reach out to you in no sound

So mysteries will weave in your mind

When I'm gone.

Stones have often been boundary markers, establishing the early parameters of territories and states. Borderlands are themselves landmarks where the cycle of so many beginnings and endings have been played out. Across the world today, borders are figured as sites of opposition, played out in war and death. Yet, borders are never just lines of concrete between opposing forces, however fortified they become. Surely, borders need to be rethought as areas of dynamic cultural interaction and where groups come together and share their differences, rather than continuing to see these spaces as killing zones. We must let the silence of the ancient stones speak, not simply of a narrative of opposition, but to and for the malleability and floating nature of contemporary borders.

The things we tend to dismiss or overlook are the things that speak the present. The ones that are most boisterous and loud are the ones that mask history. We want to go beyond the appearance of the polished, of the powerful. This way allows us to see beyond the screen of a supposedly mute and unchanging solidity, beyond the silence of the present. To do so is to see and hear an alternative form of narrative, one that listens more attentively to the silences and sees more carefully the seemingly empty spaces that make up our existence. Survival necessitates a different relationship to the elements and to those elemental things that are based on our daily interactions, on quotidian existence. Stones are not elements that belong to a permanent and unchanging history that leads, like marble steps, to the present. They are elements that are always changing, just as the present itself is always changing.

****

Thinking-through-stone reminds us of the continual crisis of the present, of its impermanence, and ours. We are constantly on the edge of living -- on the borderline of a present – that we never seem able to cross. We are under the ominous threat of survival. The discovery of carved out rocks, labyrinthine tunnels, tombs, caves are regarded as markers of the unknown “other,” and ancient civilizations are almost always seen as chiseled in stone. Thus, we are enmeshed, as if in stone, in the many aspects that make up the history of the present. The present is generally seen as a projection of the future, or as an outcome of the past. But it is not the case that when the present is finished, it is no longer there. If we understand the present as constantly existing, then the future is in the present, and the past also is in the present. The stone, as the element that is always present in all forms, and always changing, represents this persistence of the present, much more than it does the supposed permanence of past.

****

Who then speaks for the present? It is the stone itself, which recalls who participated in its carving, who carried it to a certain place, who kissed it, cooked with it, are killed with it. These Sisyphean laborers, the humblest of us all, carve the stones, inscribe the letters that shape and form our lives and deaths. These etceteras of histories, who build bridges and roads, engrave portraits and statues, erect the stones that mark graves, listen and react to the idioms of the language of stone. Those who labor without authorship attached to their names have left us a virtual dictionary that retains indelible marks and fingerprints of the memories of stone. Stones, as repositories of eloquent mysteries, affirm our various modes of being and becoming part of the wisdom of our forbearers. As Mahmud Darwish, the Palestinian poet, bemused:

We will hear the voices of our ancestors in the winds

We will listen to their pulses in the blossoms of the trees

This holy earth is our grandmother, stone by stone

Just as our ancestors, in their stone spaces, regarded the sacred history of our universe, stones call on us to participate in a mysterious sense of wonder at the interwoven nature of existence and becoming. Stones, then, are far more than materials that we use to construct our bridges and temples and mausoleums.

Stones are the epitome of that which crosses over, even though they seem to remain ever the same. Stones mark the passages between phenomena, between life and death, material and spiritual. Consider the image of a child who picks up a pebble and tosses it into pond and delights at the motion of the stone and the disruption it causes on the placid surface of the water. This primary sense of play, and its attendant notions of awe and joy, in the magic of being, are what we are attempting to evoke here. There exist spiritual forces embedded in our cultural inheritances that require us, to recast the un-thought of stone into the ripples of meaning.

In short, "Stones" are "ideas" -- in the crude paving of our thoughts. Stones are the un-written upon which spark the infinite and re-written soliloquies of meaning. They are like chants that carry prayerful inscriptions and texts that are continually at play.

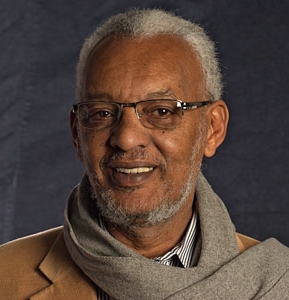

Teshome Gabriel, Ethiopian-born American cinema scholar, longtime professor at the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television, and expert on cinema and film of Africa and the developing world.

Teshome Gabriel, Ethiopian-born American cinema scholar, longtime professor at the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television, and expert on cinema and film of Africa and the developing world.