Third Cinema as Guardian of Popular Memory: Towards a Third Aesthetics

In an interview given to the New Left Review, the Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier relates an anecdote about a small fishing village in Venezuela where all the inhabitants are black. As he got to know the village people, they often told him about the Poet who enjoyed a great deal of prestige among them. The Poet had been away for quite a while, and they missed him. One day the Poet, a colossal man, reappeared. That night by the sea all the villagers, from children to old folk, gathered to hear him recite. With a ritual gesture and deep voice, he told the story of Charlemagne, in a version similar to that of the 'Song of Roland.' 'That day,' Carpentier says, 'I understood perhaps for the first time that in our America, wrongly named Latin, an illiterate man, descendant of the [slaves], recreated the "Song of Roland" in a language richer than Spanish, full of distinctive inflections, accents, expressions and syntax.'

This Poet, in a sense, replicates the anonymous legendary storytellers of traditional times. The peasant, the tiller of the soil, the traveler, the explorer and the hunter all combine the lore of the past with the lore of faraway places, to conserve and deposit into popular memory what has transpired in life and in everyday social existence.

Once memory enters into our consciousness, it is hard to circumvent, harder to stop, and impossible to run from. It burns and glows from inside, causing anguish, new dreams and newer hopes. Memory does something else beside telling us how we got here from there: it reminds us of the causes of difference between popular memory and 'official' versions of history.

Official history tends to arrest the future by means of the past. Historians privilege the written word of the text - it serves as their rule of law. It claims a 'center' which continuously marginalizes others. In this way its ideology inhibits people from constructing their own history or histories.

Popular memory, on the other hand, considers the past as a political issue. It orders the past not only as a reference point but also as a theme of struggle. For popular memory, there are no longer any 'centers' or 'margins,' since the very designations imply that something has been conveniently left out. Popular memory, then, is neither a retreat to some great tradition nor a flight to some imagined 'ivory tower,' neither a self-indulgent escapism nor a desire for the actual 'experience' or 'content' of the past for its own sake. Rather, it is a 'look back to the future,' necessarily dissident and partisan, wedded to constant change.

Folklore as popular memory

As popular memory is the oral historiography of the Third World, folklore is an account of memories passed from generation to generation. Because the promise of freedom and the recovery of autonomy of identity lingers in memory, folklore offers an emancipatory 'horizon' - a liberated and alternative future. In a world where 'logic' and 'reason' are increasingly being used for 'irrational' purposes and alms, folklore attempts to conserve what official histories insist on erasing. In this sense, folkloric traditions of popular memory have a rescue mission. They wage a battle against false consciousness and against the official versions of history that legitimate and glorify it.

Folklore is an all-embracing phenomenon which comes from people's primary relation to the land and community. It comprises the popular expression and interest of 70 to 75 per cent of the Third World population. The closer to the land, the greater the volume and activity of folkloric material. Folklore is thus grounded in the notion of balance and harmony between nature and humanity.

In this conceptual framework, the struggle between good and evil acquires a unique symbolic significance. For instance, in some specific forms of ritual dance in Africa the dancer representing evil is normally quarantined behind stick fences or is physically guarded. The removal of the one possessed by evil from the fellowship of the community is, in a sense, tantamount to death. However, once rid of the possession, the redeemed one may rejoin the group.

This notion of controlling evil, putting it in its place rather than destroying it, is in a way a critique of Western dichotomies. In the Western conception, reason is expected to dominate nature, whereas in other traditions reason is not seen as outside the scheme of nature. In the Western conception, positive and negative, self and other, subject and object are seen as distinct and separate, with no possibility of concentricity. Folkloric thinking, which collapses opposites into a unit, encourages us to be prepared for and to accept even the reality of death, because it is not considered to be outside of life. In folkloric logic, what appears to be outside of existence is always seen to be, in fact, at the very core of existence itself.

The dynamic of this logic lies in its ability to make the memory of events accessible through some form of mythification. In this way, with each passing generation, it renews and authenticates itself through popular mandate.

Third Cinema as popular memory

These, then, are the most predominant aspects of the communicative modes within the Third World. Third World cinema is only a further illustration. Third World cinema does not, therefore, have an independent existence. It is merely an index of a general cultural and historical trend in which filmmakers can find their role and serve as caretakers of popular discourse in cinema.

My intention here is not to give a unitary definition of 'Third Cinema' which can be brandished at other cinemas and other people. There can be several kinds of Third Cinema depending on the prevailing social order. On the other hand, I do believe that there are still power struggles going on, in the Third World as well as in the West. Independent filmmakers seeking representation through filmic discourse need access to power to express them. Somewhere between this access to power and representation lies the battle between history and popular memory, between cinemas of the system and Third Cinema.

As originally conceived, the impetus of Third Cinema was and continues to be participatory and contributive to the struggles for liberation of the peoples of the Third World. At present, these struggles are of two types. In those regions of the Third World where 'the battles for history and around history' are ever more intensified, the original manifesto of 'camera as a gun' still holds. The films coming out of El Salvador, South Africa and Palestine, to mention a few, are eloquent testimonies. This was perhaps beautifully illustrated in El Salvador: The People Will Win, where a fighter emerges from the jungle into a small clearing and exchanges a gun for a camera - then both protagonists clear the premises and go their separate ways. In fact the manifesto of Palestinean cinema, as with the original manifesto of 'Third Cinema,' explicitly calls for 'the establishment of cadres capable of using a camera on the battlefield beside the gun.' In such instances, Third Cinema is a soldier of liberation.

In those other regions where the major battles have moved into the cultural front, including the efforts of minorities and progressives in the West, the conjunction of cinema and struggle takes on a new dimension. Nonetheless, in whatever form, this retains similar strategies both to recover popular memory and to activate it. For this is the passion which fires Third Cinema of various types. We can therefore understand when Ousmane Sembene says of his current project, 'If I die before making Samore Toure, please tell the world that I died a very unhappy man.'

Progressive filmmakers all over the Third World have expressed a passion for defining their role as custodians of popular expression. Whether it is Fernando Birri of Argentina or Octavio G6mez of Cuba, they have not only expressed but have also shown cinematically a pronounced sensitivity to popular culture. From Julio Garcia Espinosa of Cuba to Ousmane Sembene of Senegal, from Miguel Littin of Chile to Haile Gerima of Ethiopia, the most persistent call has been sounded: that the future of cinema depends on popular culture and popular memory.

What I suggest here about popular memory in film seems to apply equally in Third World literature as well: Gabriel Garcia Marquez of Colombia, Carlos Fuentes of Mexico, Ngugi wa Thiong'O of Kenya and Ousmane Sembene of Senegal largely base their work on collective memory. In fact, all of these distinguished Third World writers have either written about films or have made their own, heralding the emergence of a new kind of cinematic discourse in which film and literature are brought together as a form of collective expression. This expression suggests that one can read literature as one reads film, just as one can read film as one reads literature. Carlos Fuentes, in a foreword to Omar Cabezas' book Fire From the Mountain: the Making of a Sandinista, says the following: "There is a strong sense of cinema in Cabezas' writing. At times I felt I was seeing one of the great Rossellini films in the streets of the open city ... with a handheld pen doing the work of the bumpy, free, gritty, handheld camera of Italian neo-realism. The liberation through language is also a liberation through images."

The degree of consistency of interest in and veneration of popular memory and manifestation in Third Cinema films is striking. Letters from Marusia by Miguel Littin is a film about the massacre at Marusia, Chile in 1907. It depicts an event not found in any official Chilean records or histories. But what happened in the saltpeter mining town eighty years ago persists in oral tradition. The filmmaker draws upon these traditional memories, utilizing the portrayal as an allegory for present-day Chile.

Similarly, Susan Munoz and Lourdes Portillo's Las Madres: the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo vividly demonstrates the contradictions between official history and collective memory in its moving account of the testimonies of mothers of the disappeared children in Argentina. Clearly, it is through attempts such as theirs that what is repressed in official versions of history is kept alive through collective accounts.

Carlos Diegues' Quilombo is a film also inspired by such popular accounts, in this case the history of a black free nation, the Republic of Palmares. This film is bracketed around the 'Goddess of the Sea,' a popular mythological figure in black folklore. The 'Goddess of the Sea' signifies African peoples' return to identity and dignity. They came by sea and will eventually sail again, both as repositories of past events and as tenacious guardians of popular memory. The 'Goddess of the Sea' therefore marks a place of meaning. It helps stimulate the hushed memories of the homeland and calls for the exiles' complete return.

Whether it is Nelson Pereira dos Santos' Memories of Prison, Tomas Gutierrez Alea's The Last Supper, Ousmane Sembene's Ceddo, Antomo Ole's Pathway to the Stars, Med Hondo's West Indies, or Miguel Littin's The Promised Land and his more recent film Acta General de Chile - all delve into the past, not only to reconstruct, but also to redefine and to redeem what the official versions of history have overlooked.

Towards a Third Aesthetics

In order to explain the ways in which Third Cinema is able to challenge official versions of history, I now turn to a discussion of Third Cinema aesthetics as an alternative to Western classical norms. Let me say a little about narrative as a mode of relation in popular memory. This perhaps might account for the character of the aesthetic factor involved.

Take a hunter and a game. In the Western-style movie, the depiction of the hunt would focus upon the ultimate act of the hunter bagging his game. In the Third World context, the interest would be in depicting the relationship of the hunter to the natural environment which feeds his material and spiritual needs and which, in fact, is the source of the game. Here we are dealing with an unresolved situation, with no closure.

Consider a film that was well received by all sectors of the Cuban populace, Octavio G6mez's Now it's up to you. The film was based on the public trial of four counter-revolutionaries who committed sabotage. Both the trial and the film end when a character says, 'Bueno, companeros, you have seen the facts. Now you have the floor. It's up to you to decide where the responsibility lies.’ These words are intended as much for the audience in the theatre as for the jury at the trial, thus conflating the film's text with the everyday reality of the spectator. In this sense, the film makes pertinent and highlights the contradictory situations of everyday life and provides a model for negotiating it. In contrast, closure in Western films contains and separates the work from everyday life.

Even those films in Third Cinema (such as Nelson Pereira dos Santos' Memories of Prison and Tawfiq Saleh's The Duped) that do contain closure are of a different nature. Their purpose is not simply a call for action, but rather an invitation to consider one alternative among many. In this way they engage and entice us with historical memories, authenticating the causes of conflict, of failure, and of difference.

Another form of Third Cinema narrative - the autobiographical narrative - illustrates this point. Here I do not mean autobiography in its usual Western sense of a narrative by and about a single subject. Rather, I am speaking of a multi-generational and trans-individual autobiography, i.e. a symbolic autobiography where the collective subject is the focus. A critical scrutiny of this extended sense of autobiography (perhaps hetero-biography) is more than an expression of shared experience; it is a mark of solidarity with people's lives and struggles.

Let me take as an example the film Acta general de Cbile, a recent [1985] and passionate instance of Third Cinema. Exiled Chilean director Miguel Littin characterizes this work as a testimony to the struggle of the people of Chile against Pinochet's repressive regime. Because of his status as a marked person by Pinochet even after twelve years of exile, Littin was forced to shoot the film clandestinely, disguised as a Uruguayan businessman. The film is organized around 'collective' instead of 'individual' points of view through which notions of subjectivity collapse. What we get instead is a blurring of identities where the addresser and the addressee are engaged in a ceaseless exchange of roles. Although Littin chooses to include himself as another persona in his own film, he can only do so in disguise, both as the filmmaker and as a participant. Metaphorically, there is a sense of irony and sadness about the self-identity of the Chilean people today in that he, a Chilean, had to take on a disguised identity to visit his own country.

Nursing his own memories, Littin muses at the crossroads of discourse not so much as an 'author,' but as a witness. His narration of the film is as much a question to himself and other Chileans as it is addressed to the viewers: "Are they [Chileans] closer to emotions than ideas today? I think about the man who on September 11 faced his solidarity destiny in order to leave his people a flag ... Does Allende live, I ask myself, in the memory of the Chilean people? Does his thought, his action, his consistency live in the memory of the people: ... it will be necessary to scratch the earth's surface to find the soul."

His personal reflection, blended with interviews and historical footage, becomes a collective testimony to the Chilean struggle, and gives a greater dimension of popular memory than is true of purely historical treatment of such issues. While in the Western documentary the individual and the social are of typically separate realms, in Acta General de Chile they are integrated to produce images of popular expression. What distinguishes this narrative structure from Western forms is its use of multiple points of view - in the process of making the film as well as in the delivery of its subject matter. The film thus stands in for a memory deferred by official history, which demands of us a new form of political awareness.

Indeed, the film stands as both a representation of popular memory and as an instance of popular memory itself. Its elaboration of several elements provides us with a quite distinct form of historical narrative, which blends typically disparate categories along three axes: 1) the constitution of the subject which is radically different from a Western conception of the individual; 2) the non-hierarchical order, which is differential rather than autonomous; 3) the emphasis on collective social space rather than on transcendental individual space. I believe that these axes, which predominate in popular memory, resonate with the cultural expression indigenous to most of the Third World today.

Furthermore, the process of making the film itself was in fact an integrated and highly collaborative endeavor. Littin organized five different crews of various nationalities, none of whom knew of the existence of the others. Each worked separately in Chile, officially sanctioned to do films which were in fact cover-ups for their actual purpose. For instance, the Italian crew was shooting a film on architecture (which gained them entry into the Italian-designed Presidential Palace), while the French crew pretended to be doing a commercial for perfume and the Danish crew was engaged in an ecological film. Footage from each crew's film was later incorporated in the overall work, providing sufficient material to produce a four-hour television program in Europe and the two and a half-hour documentary Acta General de Chile.

This collective nature extends as well to Gabriel Garcia Marquez's book, Miguel Littin Clandestino en Chile, on the making of the film. Marquez builds on, adds to, and becomes part of the collective enterprise by giving it his aesthetic literary form. In a similar way, film viewers, whether Chilean exiles or ourselves, are also introduced to the collective autobiography of events in Chile, and are urged to interact with it. These spectators' positions thus defy notions of passive viewing and celebrate direct participation. In this sense the film enters the spectator's own autobiography, awakening a reconstituted identity which allows for the sharing in and acknowledgment of the collective struggle of the Chilean people. One can imagine, then, that when the hour finally strikes - the fall of the Pinochet regime - all those who have collaborated with, commented on, and witnessed the film will realise and reflect upon their part in the making of history.

Here, therefore, is the emergence of a new cultural discourse, epitomizing the concept of 'memories of the future,' which is a predominant discursive strategy in Third World film and literature today. Generally speaking, this phenomenon, by which we collectively place our signature on historical change, can also be discussed as the emergence of a Third Aesthetics, which in my previous work I have touched on from the perspective of Third Cinema.

We are talking here of 'activist aesthetics' and 'critical spectatorship.' The relationship between the two has a distinctive form which accounts for the character of the aesthetics of Third Cinema. These aesthetics are, therefore, as much in the after-effect of the film as in the creative process itself. This is what makes the work memorable, by virtue of its everyday relevance. In other words, within the context of Third Cinema, aesthetics do not have an independent existence, nor do they simply rest in the work per se. Rather, they are a function of critical spectatorship. We consider, therefore, the aesthetic factor of Third Cinema to be, above everything else, extra-cinematic.

In contrast, the aesthetic form of the narrative in Western film culture is the aesthetic of the hero - it starts with a hero, develops with a hero and ends with a hero. This is as natural a style as breathing. Every shot and sequence of shots is governed and orchestrated around this principle. Any other character, place or decor is recognized and made visible only in relation to the hero. The hero occupies the foreground and hovers over the background - the entire screen is his or her domain. This centrality and separation of the hero is what makes him or her a ‘star' or a ‘super-star.' If Third Cinemas are said to have a central protagonist, it is the ‘context' of the film; characters only provide punctuation within it.

Of course, there have been attempts toward collective heroism in Western films, but these have mostly tended to be stories of individual heroes who somehow affect each other by fate or by accident. This kind of cultural identity, of separateness and of isolation, privileges the individual over the social and the collective. It is, in fact, the fundamental basis of difference between Western and Third World discourses. In the contemporary Western movie the theme of the story is the style of the form; in other words, these are the tools - the camera and the sets - that move the story around, instead of the story moving the tools. The shooting of the story is but a pretext for shooting the form. On the other hand, Third Cinema filmmakers rarely move their camera and sets unless the story calls for it. Here, style grows out of the material of the film.

Most Third Cinema films focus on the story as opposed to action. This deliberate choice is their identifiable quality. When there is dramatic action it operates within the broader scheme of the story rather than for the mere exultation of tempo and movement. Third Cinema films work with a sense of place and with fluidity of perspective. If they have any mood at all, it is that of a ritual or a carnival. Their meaning, however, resides in the relation of the work to its situation. Besides, the open-ended nature of the films, which accounts for the consideration of everyday life, also helps compose its aesthetic. The memorability of the work has much to do with our intellectual stimulation as well as with our sense of what is emancipatory aesthetics.

Take for example Med Hondo's West Indies. This carnival of cinema is without a hero. Its story leaps back and forth in historical time. We as witnesses are not only caught up with a reshuffling of historical documents but also, and more importantly, with the history of resistance itself. Here the camera and the sets are partners in the festive call to revolution. The film thus recognizes and dismisses us as spectators at the same time. We are recognized in so far as we respond to the festivities as a call for revolt; we are dismissed if we merely cheer and celebrate its dance and song as vicarious entertainment.

The aesthetics of criticism

Today, some critics dwell on the role of mediation in criticism and claim to occupy the center of discourse, marginalizing all others just as official histories do. But there cannot be mediation without ideology, or criticism without consensus. It is futile to skirt this issue. We know that every spectator mediates a text to his or her everyday situation. Attempts to homogenize difference by networks of mediation are therefore doomed to failure.

It is clear that what is central to mainstream criticism is that other alternative discourses, particularly those considered 'marginal', might reveal the ideological undercurrents that critics are trying to conceal. They insist upon erasing alternative discourses with one purpose only - to maintain their power of domination. But the distinction between ‘center' and 'margin' is no longer relevant when these critical practices are understood to be merely one of various alternative discourses.

Under the structuralist-semiotic impulse the diachronic study (the study of art-works over time) has fallen into eclipse. Structuralism and semiotics offer a synchronic account of the internal structure of the text without its relation to the generic tradition in which it is situated. In other words, the semiotic-structuralist impulse represents an abstraction and rarely does address the question of reception (i.e. how the work appears to spectators). Rather, it seems only to address the text. Thus this kind of criticism describes the features of the story or the text as organized by its formal elements, separating the work from its social context. This minimalizes and diffuses the political nature of the text and, therefore, allies itself with official histories.

What then should be the role of criticism in all the interlocking phenomena of Third Cinema and its aesthetics? To answer this question we need to go back to the logic of the folkloric manifested in the interaction between the performers and the listeners, which accounts for a unique cultural and aesthetic exchange. While the performers, at any given time, hold sway, it is in fact the listeners who have the power of criticism in the aesthetic Judgment of art and performance. These artist-critics are both the producers and the consumers of the work.

What then is the role of criticism regarding Third Cinema aesthetics today? I believe that there is a significant continuity between forms of oral tradition and ceremonial story-telling and the structures of reception of Third Cinema. This continuity consists of a sharing of responsibility in the construction of the text, where both the filmmaker and the spectators play a double role as performers and creators. Together, they construct an ongoing consensus of cultural confirmation through the affirmation of shared memory.

What is a critic anyway, except a story-teller? The only difference is that while story-telling in the traditional sense is more oblique, the critic's discourse is didactic and self-professed by a commitment to a position. In any case, the critic does not necessarily have a privileged access; but he or she is certainly interpolated by ideology.

A critic who is sensitive to the form and meaning of Third Cinema and aesthetics must be aware of the relationship between the work, the society and the popular memory that binds them together. Aesthetic judgment is a consensus between the critic and the audience. Thus critics who are mindful of the relationship of works to the people must seek a liberated future and necessarily take up another, more subversive position.

Let me take such a position to reintegrate a classic screen figure into the social and political context of popular memory. Recall Mantan Moreland, the black man who was well known for his gleaming teeth, his popping eyes and his quivering legs, and who has been labeled 'the accepted USA idea of the Negro clown supreme'. Who was this Mantan Moreland? Official film histories give us no clue beside the label they have attached to him. But long before he became a household Hollywood stereotype, Moreland was a young man living in Monroe, Louisiana, a state where white terror was rampant. When he was only seven years old, he had seen his shoeshine friend hung from a nearby post, his uncle's burnt body dragged down the street, and five black bodies hung dead. So at an early age his eyes rolled and his legs trembled, not because he thought one day Hollywood would discover him, but because he lived in an atmosphere of terror.

The animal that Hollywood tried to create was simply a confirmation of their racism, and the spectators' laughter at the very creation of their own myth was no less than a fulfillment of their racial fantasies. But viewing it as we are now, the spectacle, stripped naked and revealed, can be seen as finally turning upon itself - the fiction thus becomes non-fiction. And the spectacle, by trying to make 'beautiful' and 'lasting' the actual substance of a nightmare, itself becomes the nightmare.

Once the mask is removed, Moreland's identity is put in place and regains in death what was denied him in real life. His private life, now shedding the screen persona, is introduced into the social body. This, then, is one of the ways popular memory is made to carry out its rescue mission.

Conclusion

Between the popular memory of the Third World and the willful forgetting of the West, the gate-keepers of the corridors of discourse cannot be but men and women of courage and of conscience, committed to an urgent, activist cinema - in a word, Third Cinema.

In a recent film, Witness to Apartheid by Sharon Sopher, we have an account of tortured bodies as memories. The film portrays excessive violence and brutality on the part of the South African police. In several telling sequences young South Africans show body wounds that were stitched without anesthetic, as a form of torture. In one instance a young man was even able to move the skull-plate on the top of his head, which had been broken by the police.

These violated and tortured bodies, more than any written form, reveal the law of the land. But in another sense they mark the index of a world yet to come. For the flip-side of such memory, born out of suffering and pain, is ferocious and unyielding. These young South Africans, though physically brutalized, openly confess their determination to fight back even if it means joining the ranks of those who have already fallen. We are thus witnessing the re-emergence of new persons in Africa, who perhaps represent the climax of a long struggle that began with the invasion of the continent, and the kidnapping of her sons and daughters to faraway places, five hundred years ago.

This example makes abundantly clear that it is perhaps time to re-think and re-evaluate our understanding of our intellectual activity. The intellectuals are our neglected poets, filmmakers, historians and anonymous fighters, who have shown that the true slums and ghettos of the world are not those we define economically, but rather those in the minds of us who lose sleep because of the fear of the hungry and the dispossessed.

The 'wretched of the earth', who still inhabit the ghettos and the barrios, the shanty towns and the medinas, the factories and working districts are both the subjects and the critics of Third Cinema. They have always '[smelled] history in the wind'. Third Cinema, as guardian of popular memory, is an account and record of their visual poetics, their contemporary folklore and mythology, and above all their testimony of existence and struggle. Third Cinema, therefore, serves not only to rescue memories, but rather, and more significantly, to give history a push and popular memory a future.

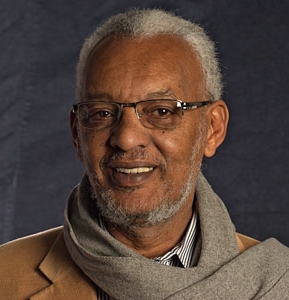

Teshome Gabriel, Ethiopian-born American cinema scholar, longtime professor at the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television, and expert on cinema and film of Africa and the developing world.

Teshome Gabriel, Ethiopian-born American cinema scholar, longtime professor at the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television, and expert on cinema and film of Africa and the developing world.